(I seem to have spent forever over this next set of posts, or, rather, not so much over as hovering – or havering – nearby. Many other duties, including a talk on one of the poets mentioned below, W.S. Graham, intervened, but I couldn’t let the occasion of Leonora Carrington’s birthday pass without some gesture.)

Last year’s unedifying political/ecological scene often made me feel like the nap of the universe was against us (‘us’ meaning the planet, not the species), so a benign-looking coincidence could work a little like a counterspell or blessing. Late last year, I was struck by a run of one film and two television programmes that seemed to hold something like a positive meaning.

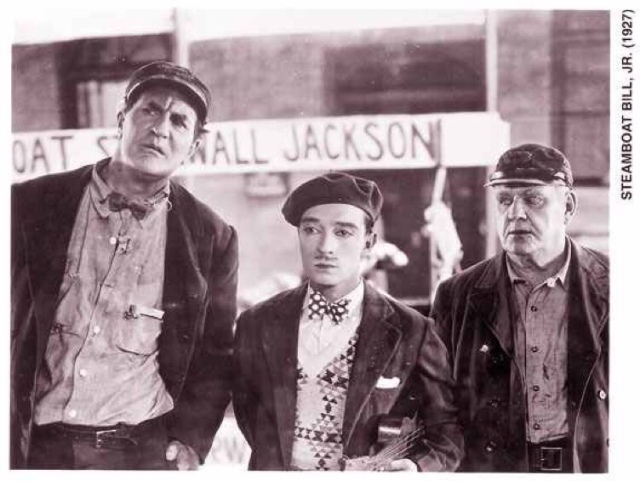

I was heading up to Dundee one Saturday in early December, when I realised that the DCA were screening Steamboat Bill, Jr that evening, with a live piano accompaniment by Neil Brand. This was followed on the Sunday night by a documentary on Leonora Carrington, directed by Teresa Griffiths. Then, later that week, on my return to Newcastle, I happened to catch another documentary, this time on Spike Milligan, Love, Light and Peace, produced and directed by Verity Maidlow, which focused on home movies and intimate interviews.

Each of these figures had, at different times, had a significant influence on me. So this concatenation felt like a prompt to take stock, as the year turned, on what such strong influences, as disturbing as they can be delightful, might actually mean in that broader sense of what you’re doing with your life, in addition to your creative work.

Certainly, in all three cases, the relationship or dialogue between the work and the life is part of the interest. Equally, with reference to our cultural and political era, it seems significant that, although each is strongly associated with a particular time or mode – silent comedy, surrealism, post-war anti-establishment comedy – none of them seems to be fully defined by such a grouping.

Rudi Blesh’s biography of Buster Keaton had bowled me over in full-blown slapstick style in the mid-eighties, defining Keaton as a sort of obsessive, damaged, naive surrealist which I connected to my engagement with figures like W.S. Graham and Ivor Cutler, an engagement which itself stemmed from my teenage obsession with the traumatised absurdities of Milligan. Carrington I’ve tried to speak about in several posts without ever quite defining how the blend of no-nonsense briskness and the embodiment of something utterly nonsensical and other in her art and her writing affects me – a situation she would have regarded as entirely appropriate.

Neil Brand’s introduction to Steamboat Bill, illustrated plentifully with clips from Keaton’s other films, placed a similar emphasis to Blesh on the strange pressures of being a child star in vaudeville, on his improvisatory yet methodical explorations of the techniques and technology of early silent comedy, and on the industry’s inevitable rejection of Keaton, as film-making became a matter for producers and career paths, rather than an avant-la-lettre auteur who wouldn’t initially have understood what an auteur was.

Back in 1985 or 86, I wrote a sequence of poems called ‘A Dream of Buster Keaton’, which was published in Poet & Critic in the US. This marked the first substantial appearance of my work in English outside the context of student mags – except it being published in the US meant no-one in the UK really saw it till the sequence was reprinted in my Arc collection, The Testament of the Reverend Thomas Dick, in 1994.

By then I was reading Leonora Carrington’s short fiction, reprinted by Virago in the late 80s/early 90s, including the collection The House of Fear, which cast its odd light on how I felt about the tiny degree of exposure which my work was then generating. My literary and academic career throughout the eighties had been fairly unremarkable, but here I was in that first flush of attention where your books are noticed and you begin to be asked to perform those public duties of performing, reviewing, and teaching, of presenting your (or, at any rate, a) self. I had been, slowly, picking up residency work, and I would soon lecture for a sort of living in an actual university…

But, even though this was happening at a very gradual rate, and the ‘exposure’, such as it was, would drop to a minimum within a few years, in favour of those more suitable for the kind of success on offer, I rapidly realised that something in me did not really want to be seen.

This was not the same thing as not wanting to write or perform my work – or indeed to discuss others’ work – or to be acknowledged. I just shied away at a level that felt like an an instinct or a phobia from How Things Are Done. What Keaton, Carrington, and Milligan suggested for me, then, were ways of evading not especially that fleeting gaze, but rather the categories it put me in.

Although my creative space overlapped with the public realm of publication and presentation, of mingling and the marketplace, pitching and schmoozing, only a tiny sliver of it did so comfortably, and the rest preferred distance and therefore accepted obscurity, or Secondariness.

Hitherto, my non-career had enabled me to preserve the illusion that all was going splendidly – a decent degree, a small circle of literary associates, some publications – I could breeze over the broken ‘marriage’ and the almost-abandoned PhD. It wasn’t until, with my second wife’s help, I started to get my life together, that I understood how committed I had become to not being togethery, to not really being ‘there’ at all.

Now not only could I hear the stupid words coming disjointedly out of my own mouth on TV and radio, but also people could not give me those jobs I’d just assumed I’d drift into. Now I actually had to look after a family rather than have my family look after me.

I’m describing the series of stuttered moments at which I began to wake up from the Arrogance, that survival mechanism which ensures you never need to face doubt and your own limitations, nor grow up. But of course the problem here was that I couldn’t quite grow up. Like Steamboat Bill Jr., who meanders back to the river of his birth with a beret and a silly moustache, poor puer aeternus, it seemed to be the ‘junior’ part that defined me.

In that movie, it’s not until the end that Bill Jr. has to prove himself to Bill Sr. Except, out of the frame which insists life is narrative, you can’t always prove anything, to yourself or anyone else, nor are you able to rescue Big Bill from the sinking jailhouse in the nick of time – sometimes the jailhouse simply sinks.

Sometimes, as Leonora Carrington states at the end of ‘Down Below’, once you leave for Mexico City, you never see your father again. Sometimes, as Milligan did, you discover in a letter after he died, that your father suffered all his life from the same crippling depressions you do, but never said a word.

Sometimes, as I’ve been attempting to explore in recent posts about my father, bereavement means you realise where your identity has positioned itself in relation to those other identities of family – parents, partners, children, relations, friends, peers – and understand it is not, as it were, where you thought you’d left it. But that this position seems to have become crucial to that thing you do, the writing.

Whether this is a good or bad thing has sent me back to my triumvirate of artists, to look again at what enabled and what inhibited their work, and, equally, what enabled and inhibited its reception. To watch is, for the passive, to be influenced. To watch how you are watching, then, is to engage with, adapt, and, where necessary or possible, resist that influence.

There is a famous moment where the concussed Bill Jr. wanders out of a house in the middle of a cyclone, only for the whole frontage of that house to tip down on him. He is of course standing precisely where the upper window is, and is saved by being just there, or by just being there – by being, momentarily in the story and forever on film, framed. Here Keaton alludes to and inverts a memory of childhood, in which he describes being plucked out of a window by a cyclone:

‘…I was awakened by the noise of a Kansas twister. Getting up, I went to the open window to investigate the swishing noise. I didn’t fall out, I was sucked out by the circling winds of the cyclone and whirled away down the road. I had rolled and revolved about a block from the farmhouse when a man saw me, rushed out, scooped me up, and carried me to the safety of the nearest storm cellar.’

Another scene in Steamboat Bill, Jr, just preceding this, is less spectacular, but, perhaps, just as resonant. Having been taken to hospital, Bill Jr. is lying in bed when the entire building is torn away, leaving just the rows of beds. Blown down the street as though in a self-driving automobile (the motif of machines and other contraptions literally auto-mobilising and driving themselves recurs in several Keaton movies), the bed sails into a stable.

The horses look at Bill Jr. – it is at that moment we realise there is a certain equine quality to the famous ’Stoneface’; that it is in fact the long face of that joke featuring a horse and a barman – and Bill Jr., bewildered but bewilderedly at one with them, looks at the horses. Then the stable door blows open, and the bed bolts for it.

It is, obviously, like a dream. Less obviously, it echoes the situation of Little Nemo in Winsor McCoy’s cartoon of that name, which ran from 1905-13, the first and last frames of which tended to show its titular hero in bed. Even less obviously, it rhymes with the central character’s position in Leonora Carrington’s short story ‘The House of Fear’, who finds herself going with a horse she has just met, and a number of his very frightened equine friends, to a party at Fear’s Castle:

‘The horses all shivered, and their teeth chattered like castanets. I had the impression that all the horses in the world had come to this party. Each one with bulging eyes, fixed straight ahead, and each one with foam frozen around its lips. I didn’t dare speak, I was too terrified.’

As Milligan wrote in a sketch excerpted in Love, Light and Peace:

‘Horses don’t play the piano.’

‘He’s not a real horse. There’s a dog inside working him.’